Published in Caves and Karst Science: The Transactions of the British Cave Research Association, Vol.50, No.1. p.48.

Offa’s Dyke National Trail

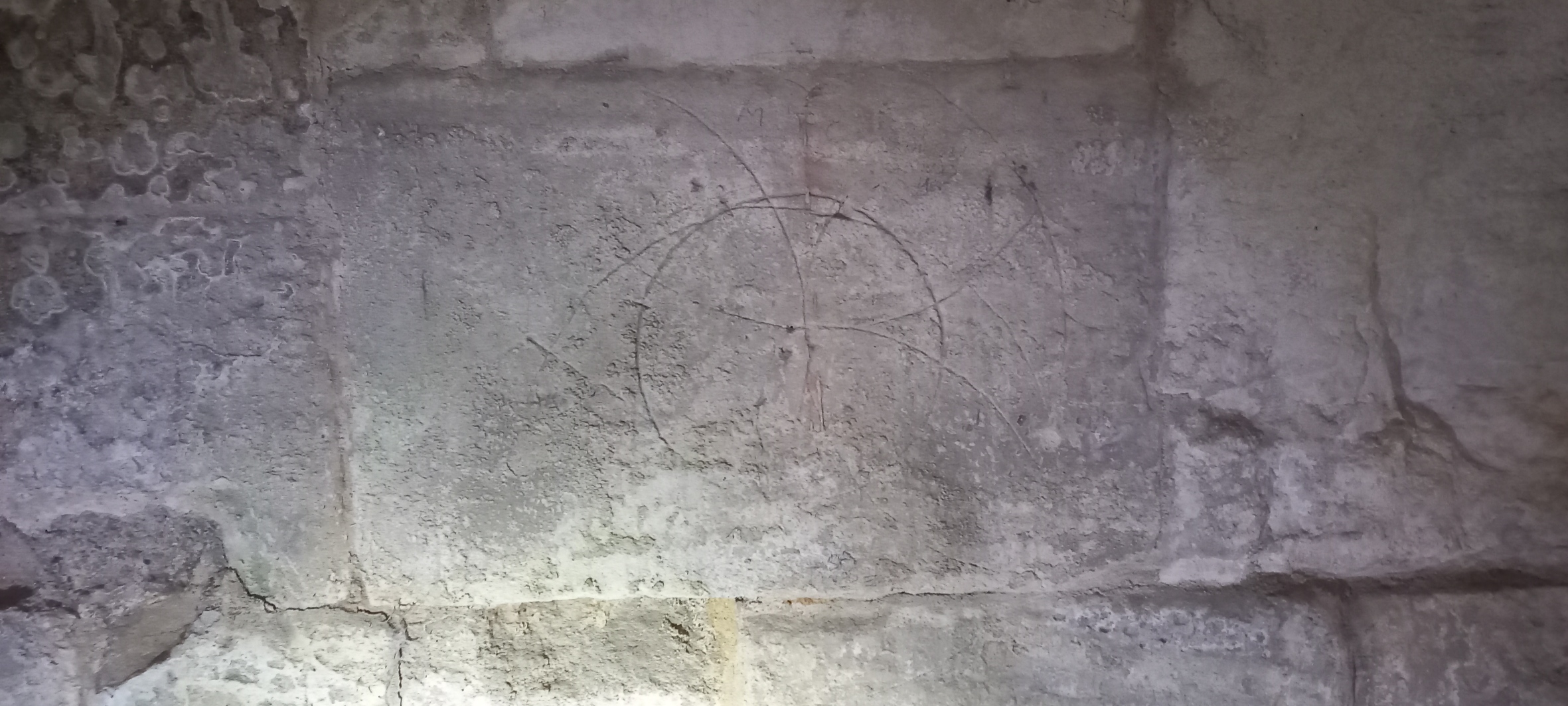

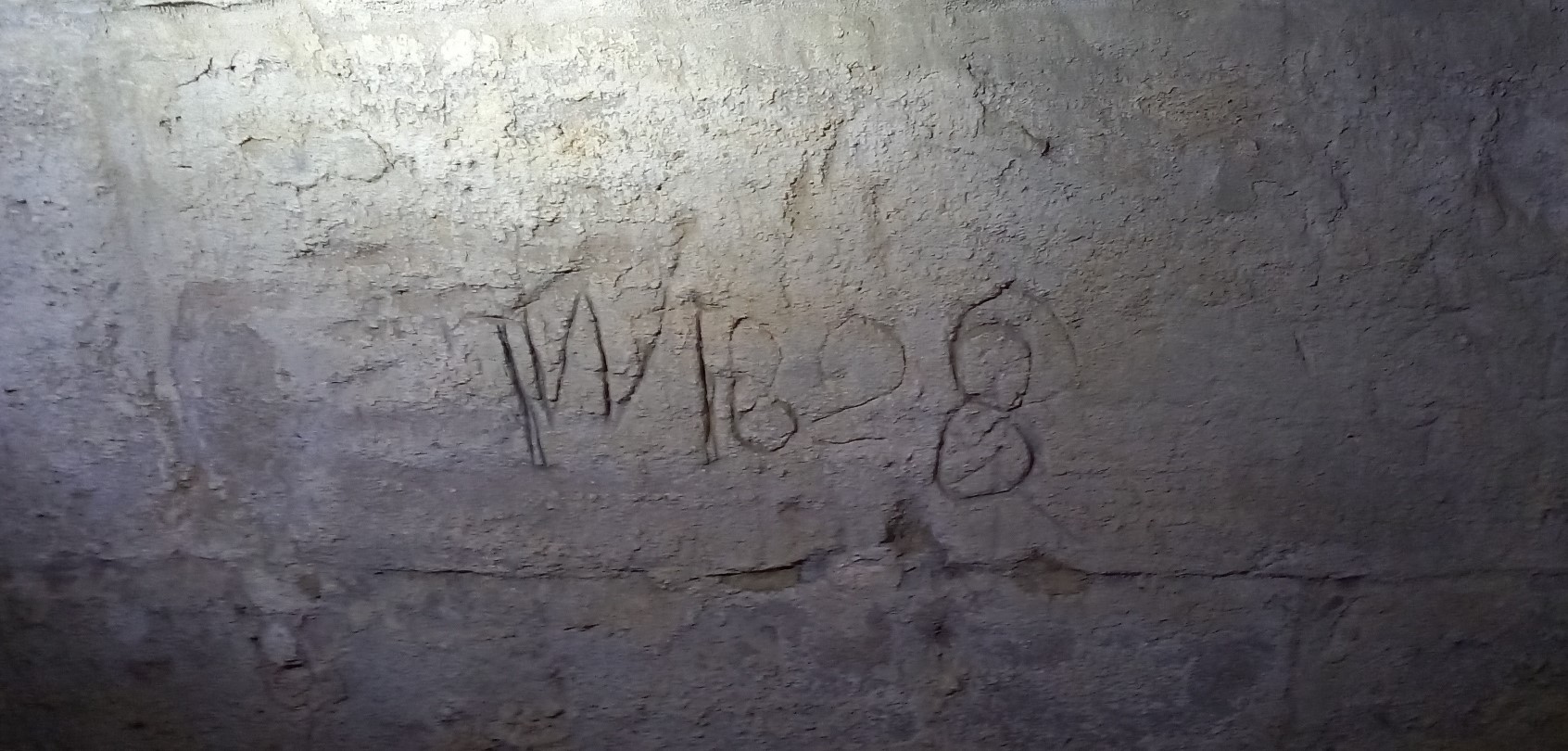

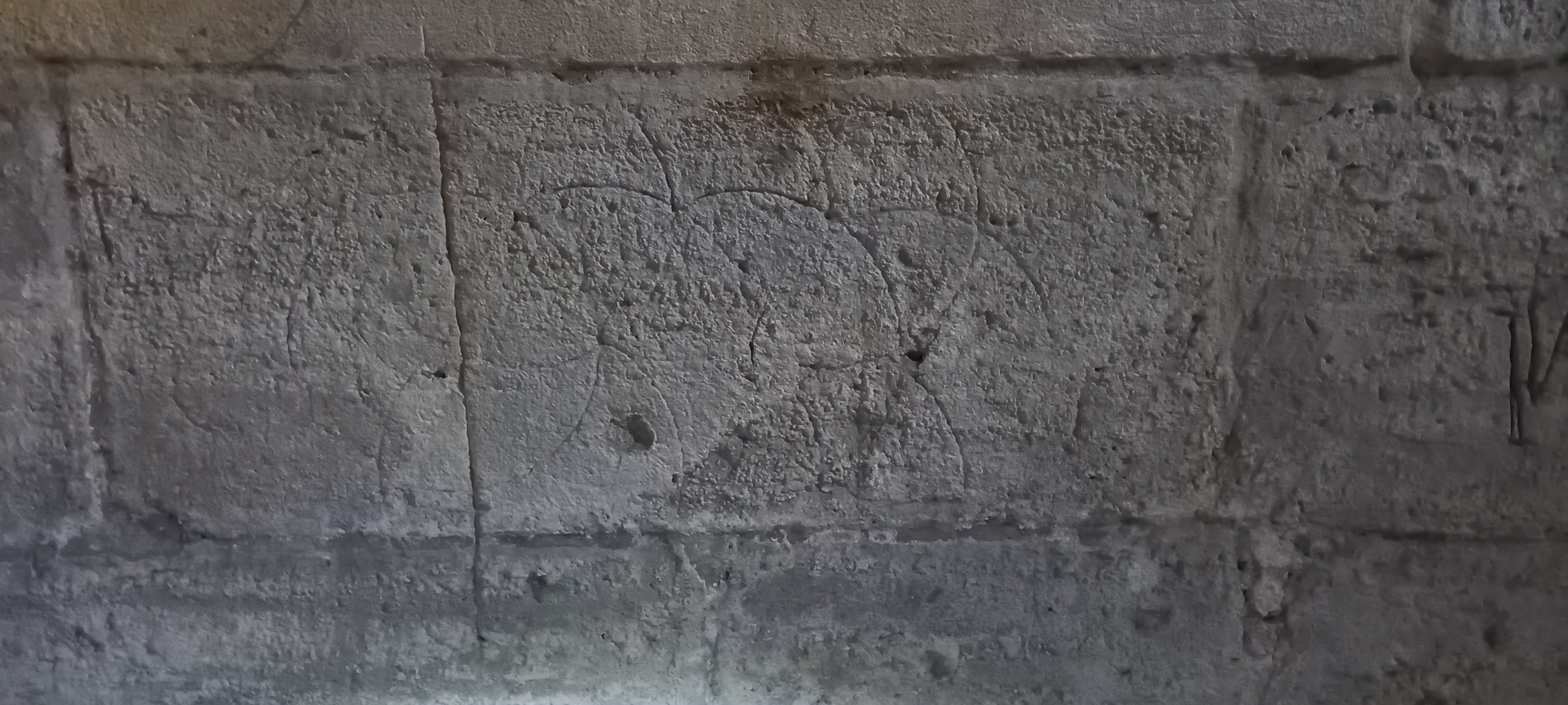

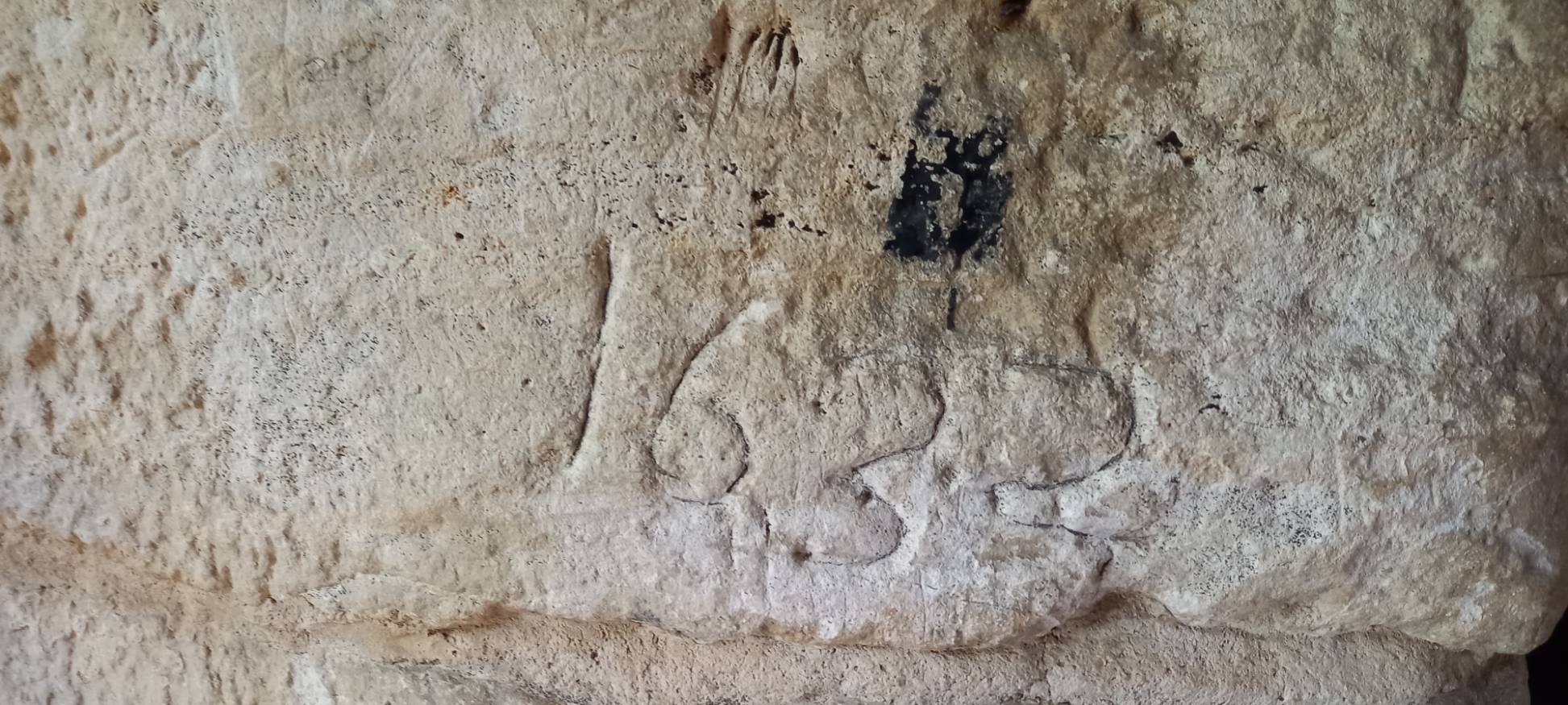

A 15th century inscription at Dead Man’s Cave, Giggleswick in the Yorkshire Dales.

Published in Cave and Karst Science, Volume 49, No.3, p136. December 2022

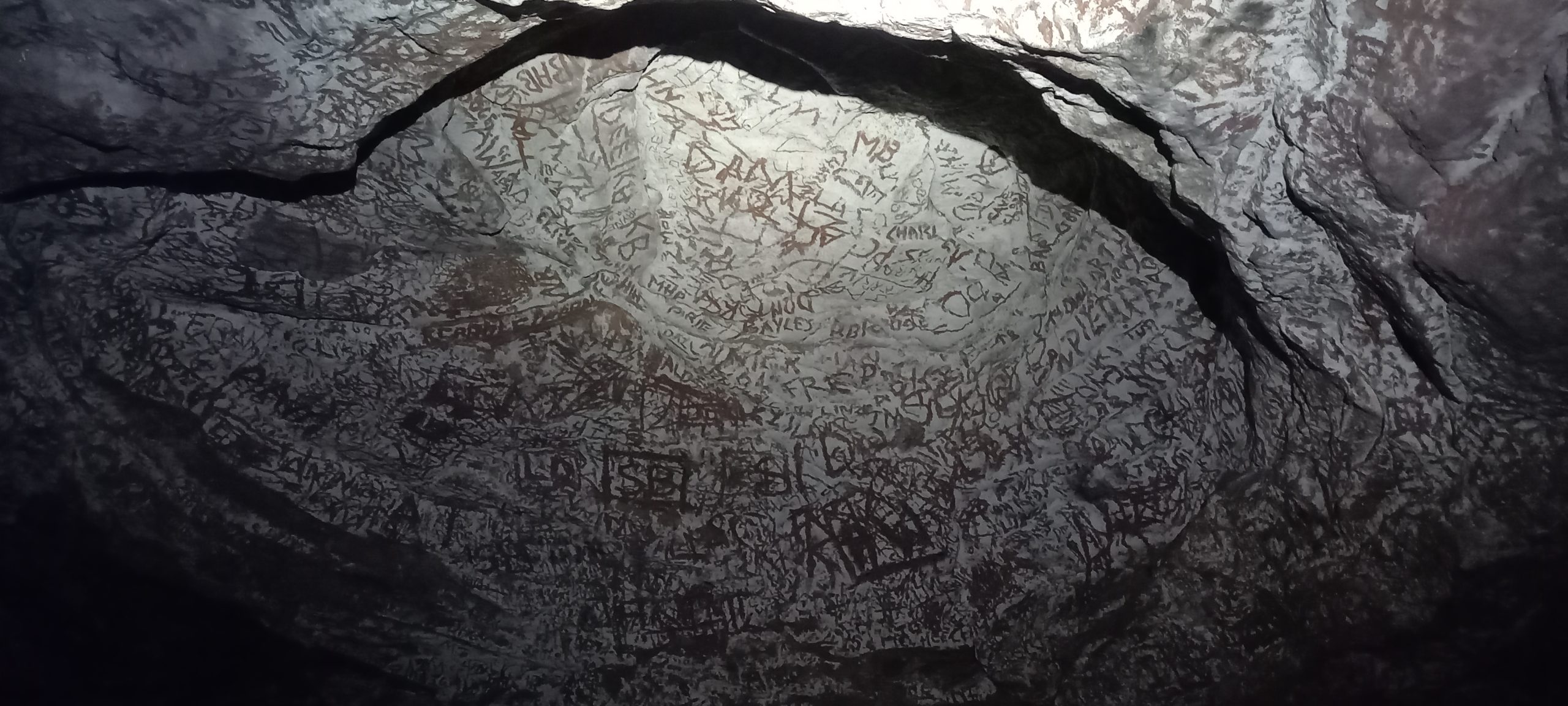

Dead Man’s Cave (NGR SD 800 670, Alt. 328m OD). The cave is situated within an area of ‘Access Land’ and is located above the scars to the northeast of a footpath between Feizor and Stackhouse. A wide entrance in the side of a grassy hollow leads to a roomy passage which closes down to a calcite and clay choke. The cave length is approximately 12m (Brook, et al., 1996).

A visit to the site in June 2022, as part of a weekend field meeting organized by the British Cave Research Association (BCRA) Cave Archaeology (CA) Special Interest Group (SIG) had identified a wealth of historical markings at the site (Simmonds, Wilson, and Hall, 2022).

The cave entrance contains an abundance of incised markings on both of its side walls, the earliest inscription dates back to the 15th century – 1461. During the medieval period, the upland meadows that surround Dead Man’s Cave were used for summer grazing, when the cave would have offered a suitable place for shelter and storage, also providing a possible context for the medieval date and its associated initials (Simmonds et al., 2022).

However, the date itself has enormous historical significance in that it corresponds to the year of the infamous ‘Battle of Towton’, the site of which is located some 50 miles to the southeast of Giggleswick (NGR SE 478 386). The political instability of the mid- to late-15th century led to a series of Civil Wars, now known as the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485), as rival factions of the House of Plantagenet fought for control of the English throne. The rival Kings in this period of English history were Henry VI of the House of Lancaster and Edward IV of the House of York.

According to English Heritage (1995) “…Although some historians have expressed doubt about the numbers that were eventually involved in the Battle of Towton, it is clear that the two armies were of an exceptional size for those times. There was a sharp fight at Ferrybridge on the River Aire on 28 March, which the Yorkists won, followed by the largest battle of the Wars of the Roses at Towton the next day. After ten hours of the severest fighting King Edward’s men emerged victorious. King Henry and Queen Margaret fled northwards to Newcastle and from there to Scotland, to continue the war as best they could. The presence of over 100,000 men and upwards of 28,000 deaths makes Towton the largest and bloodiest battle ever fought in England.”

References

Brook, A, Brook, D, Griffith, J and Long, M H, 1996 (Reprint: first published 1991). Northern Caves, Vol.2: The Three Peaks. [Burnley: Lords Printers.] p.42.

English Heritage, 1995. Battlefield Report: Battle of Towton 1461. Accessed 31 October 2022: https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/listing/battlefields/towton/

Simmonds, V, Wilson, L J and Hall, A, 2022. Meeting Report: British Cave Research Association (BCRA) Cave Archaeology (CA) Special Interest Group (SIG) Field Meeting based at Lower Winskill, near Settle, Yorkshire Dales. Cave and Karst Science, Vol.49, No.2, 80–83.

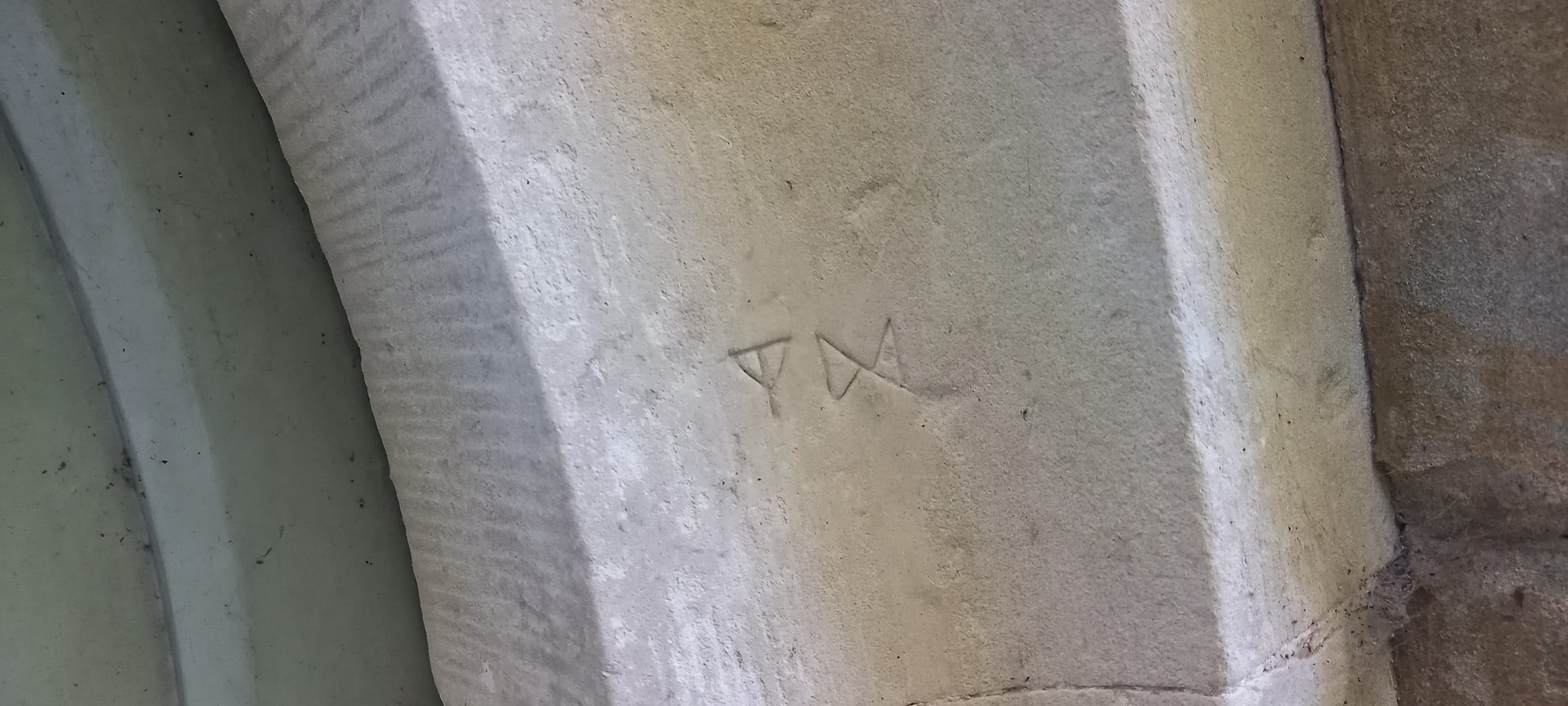

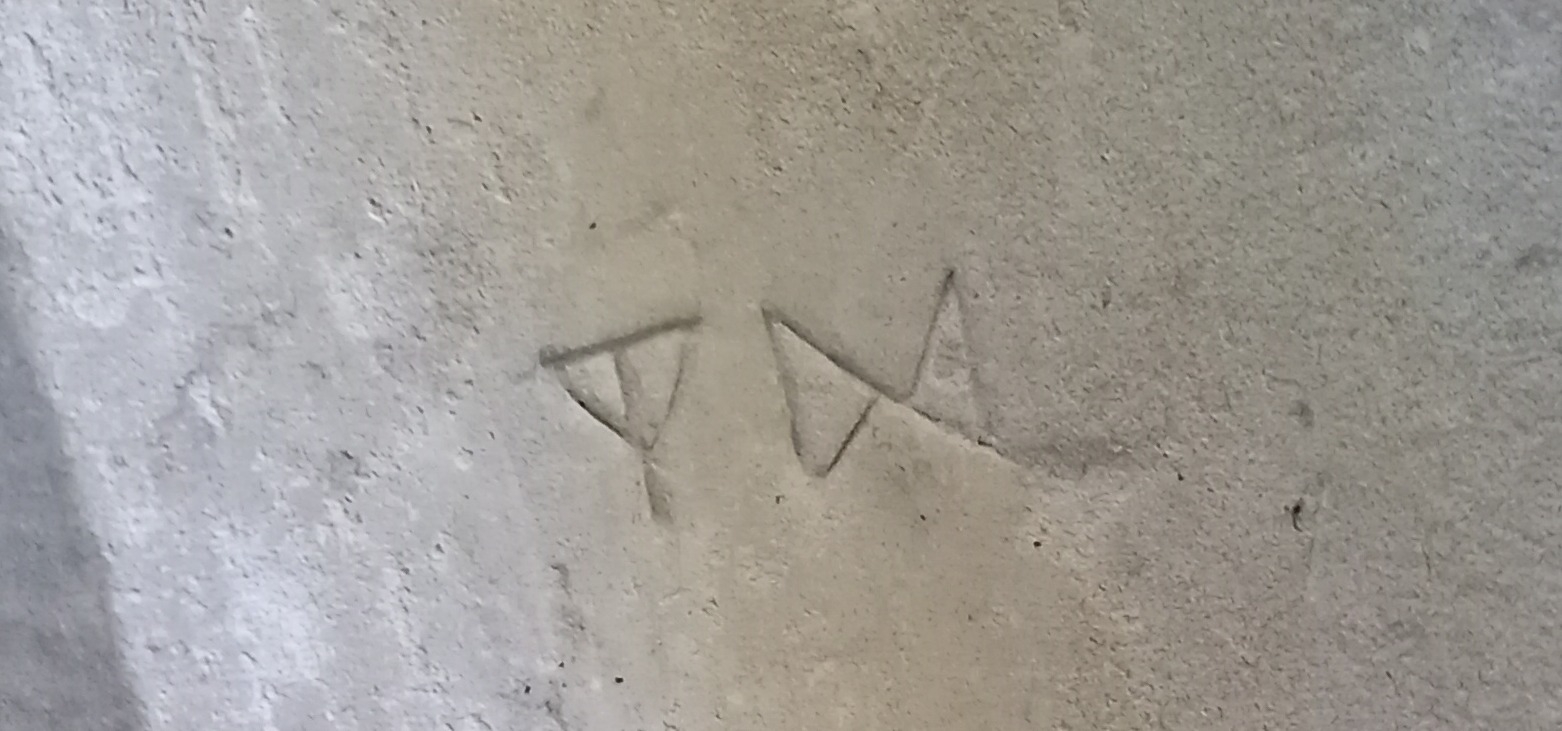

Teffont Evias, Wiltshire

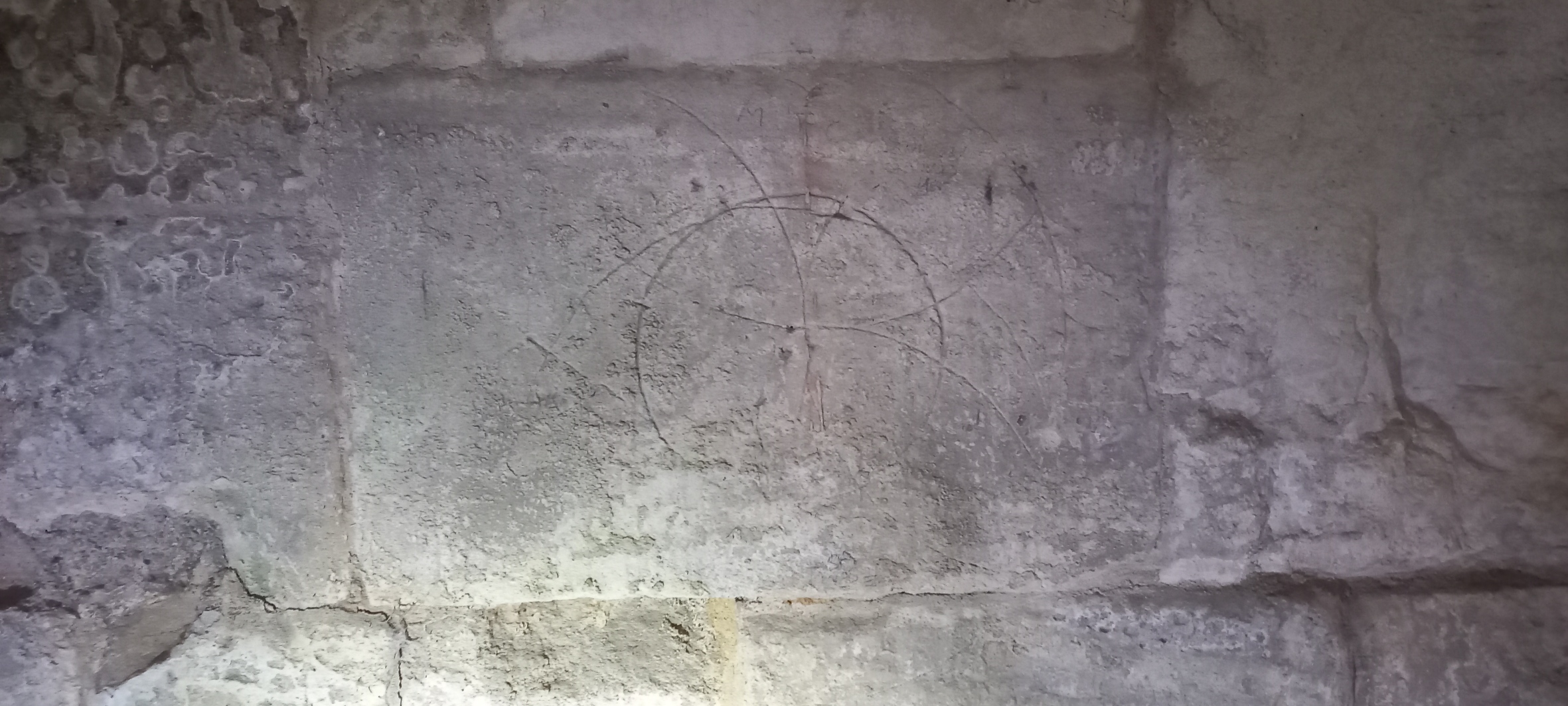

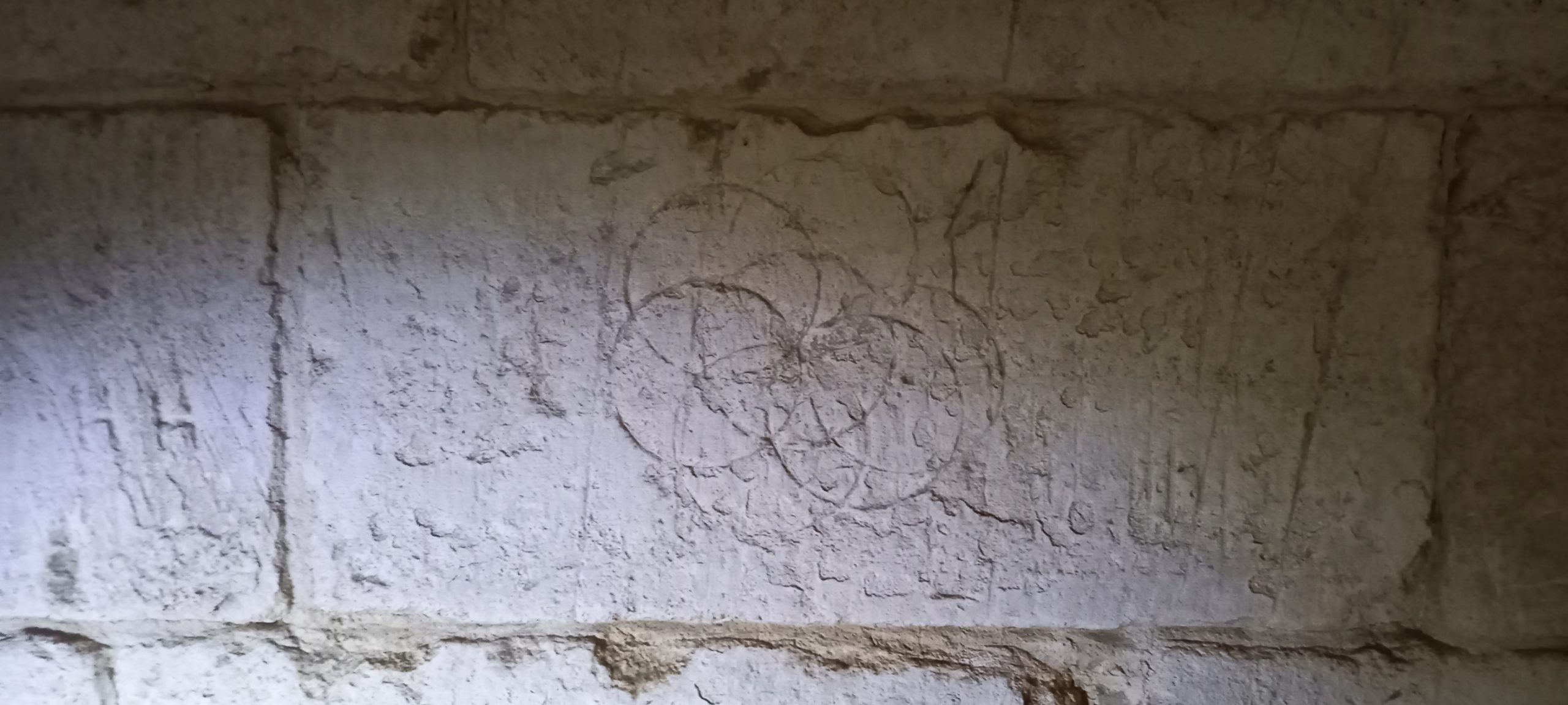

11th January: A very brief stop on the way to a watching brief nearby at the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Teffont Evias, Wiltshire. Several inscriptions were found around the doorway into the tower.

Some sets of the above inscribed ‘initials’ were noted more than once around the tower doorway. There were other less well defined markings too. The church warrants closer scrutiny another day when I have more time.

White Spot Cave, Cheddar Gorge.

White Spot Cave, Cheddar Gorge, Somerset [NGR ST 4740 5443] described as a large rift-like entrance with a steep 12m descent for which a rope is useful (www.mcra.org.uk/registry/sitedetails.php?id=768)

Thought I would visit this site located in Cheddar Gorge near the reservoir to check up on possible graffiti and other markings. However, on approaching and accessing the cave entrance, I was struck by the overpowering stench of human excrement and urine, the cave floor also strewn with litter, mostly empty cans and tissue paper. Not a pleasant place to be! I could only manage a quick scan of the walls before deciding to leave. Graffiti noted was mostly modern (2020s) and of no interest. Normally I would clear litter but in this case I felt it was too unhygienic to do so!

Cheddar Gorge, Mendip Hills, Somerset

29th November: Fog, frost, sunshine, and goats. A midday walk around Cheddar Gorge.

Home Close Hole, Mendip, Somerset

The Passages described below, in total, measured 499m and the digging team were judged winners of the 13th J’Rat Diggers Award (all members of the Shepton Mallet Caving Club, SMCC) on the evening of 19th November 2022.

16th October

Well! It has been quite a while since my last visit to Home Close.

With Callum Simmonds, Samuel Hill, Alex Hannam (all SMCC), and Duncan Price

A few weeks ago, I was having a conversation with Callum about Wigmore Swallet. He and his chums from the Shepton Mallet Caving Club (SMCC) had been busy in Wigmore reopening access following a slump in at the entrance and further into the cave the Hernia Pot area. They were keen to find somewhere to dig so I suggested they should have a look at Home Close Hole. I gave Callum my set of keys along with some pointers to some potential dig sites including the “60 metre” crawl and the gravel choke at stream level Nick and me along with others had occasionally scraped at. It was always wet and muddy. After a concentrated digging effort Callum and the SMCC team broke through into a significant section of cave.

I decided to take up Callum’s offer of a tagging along on a survey trip with some of the team to take a look at the recent extensions to the cave. First, I had to sort out some kit (I had given my neo-fleece to Callum to make his digging trips more comfortable) and I had to search for a lightweight wetsuit. I could not find my old ‘surfing’ one but, eventually, found something suitable, all I had to do now was to dig out the SRT kit. Then drove up to Wigmore Farm to meet the others. All changed walked over the fields to the cave, gate open, and down the ladder we climbed. Quickly down the pitch, all assembled and off to the former gravel ‘choke.’ Good effort by the lads to dig through a series of low, wet, grovelling squeezes requiring helmet off and a wet ear. The low section opens into a reasonably lofty rift following a mineral vein with a couple of avens. The avens had some fine clean exposures of conglomerate and several other interesting geological and geomorphological features that might warrant further investigation. At the second aven, a ladder climb leads up into a continuation of the rift (still following the mineral vein, trending approx. north/south) until it appears to close down at a boulder choke. An inspection of the choke plus removal and rearrangement of some rocks revealed a possible continuation that needs following up at a later date. Duncan and Alex surveyed along a low crawl leading to another aven while Callum and Sam dropped a ladder down into a lower continuation of the rift that soon closed down. It will need to be surveyed. I occupied myself enlarging an awkward wriggle around a bend in the low, meandering crawl before we all headed up to join Duncan and Alex in ‘Crown’ Aven. So named due an interesting chert/silicified feature at floor level. From the aven, several lengths of scaffold tube were dragged through the crawl to the rift, these might be usefully employed in the end choke. That was it really, so we made our way out of the cave back to the surface. A fine trip and well done to the diggers for the effort.

Surveyed length of passage c.325m, a significant find indeed!

17th November

Back again to look at another discovery by the youngsters, this time down in the Wigmore section.

With Nick Hawkes, Duncan Price, and Max Fisher

09:00 meet at the farmyard. Various bits of kit were decanted into bags to make a 4-way split. The plan was for Max and Duncan to install staples up the climb to the new stuff above Slime Rift. Nick and I were going up to have a look at BFC (Big Fucking Chamber) and postulate on its origins. Mostly steady paced trip through HCH to the pitch although I did think this section could do with a clear-out of tat and crap. Down the fine pitch and along the crawl to the Wigmore connection. Wet through Young Bloods Inlet (water levels were reasonably high following recent rain), up over the Generation Game and down to the excellent stream passage to Slime Rift. Max and Duncan got on with their mission, me and Nick climbed up to BFC. It was a much longer climb than expected amongst a jumble of large boulders and blocks seemingly held in place by copious amounts of mud. There are several mineral veins present and frequent faulting. We arrived at our destination, and it is indeed a “big fucking chamber”, very impressive (dimensions c.40m x 20m).

A domed, arched ceiling span criss-crossed by mineral veins, above an expanse of fallen blocks of [mostly] conglomerate with plenty of red fine sediment (silt and clay). There were boulders of calcite (including dogs tooth spar) here and there too. The large breakdown chamber has been formed along the unconformity between Carboniferous limestone shales and Triassic conglomerate. A small pocket of possible cryogenic calcite was photographed and sampled. My efforts to take photos of the wider chamber were largely unsuccessful. The chamber was filled with steam, and I had insufficient lights to fully illuminate the wide expanse. An excellent find.

Nick and I finished looking around climbed back down to join Max and Duncan, who had just completed their task. We tried out the staples and found them to be satisfactory. Time to exit the cave. It had been a very good trip.

An overnighter at Rowberrow Cavern

NGR ST 45954, 58022. Scheduled monument, listed entry no. 1011926

13th November: A local walk to try out some new kit recently purchased including a 1-person tent (Alpkit Soloist) and backpack (Deuter Speed Lite 25Litre) and a borrowed pair of OEX X-lite Pro carbon poles. Got my bag (weight18kgs) packed ready to go but allowed myself to be distracted by live rugby on the box, Scotland vs New Zealand, the All Blacks won, of course. Eventually at 16:37, I set-off on my walk, it was soon dark. Set my head torch (Fenix HL40R) on the lowest possible setting which was fine until I got into the woods and approached Rowberrow Cavern. Over the top of Mendip, Beacon Batch and Blackdown there were excellent star gazing opportunities, and several constellations were identified. Found a suitable sheltered spot to pitch the tent, then supper and a cup of tea before getting my head down for the night.

14th November: Awoke early when my alarm went off at 06:00. It was so peaceful listening to the water dripping inside the cave, the rustle of leaves in the wind, the hooting of owls, and I was very comfortable. The tent was plenty spacious enough for one-person and kit, it is roomy enough to be able to sit and write notes (or read if you had a book). My first impressions are that I am very satisfied with the tent. Decided to start sorting stuff out by 07:00, kettle on for coffee and porridge. Tent packed away; kit stuffed into my backpack, and off on the way home. Returning by the same route, this morning I should get some views. At Hazel Manor caught a glimpse of a muntjac deer. The forecast rain held off, in fact, it was decent weather for walking; dry, breezy, and mild for the time of year, no need for a raincoat.

Walking stats: c.29km, 6.75 hours total time, c. 760m elevation gain.

Some info regarding Rowberrow Cavern:

Palaeolithic caves and rock shelters provide some of the earliest evidence of human activity in the period from about 400,000 to 10,000 years ago. The sites, all natural topographic features, occur mainly in hard limestone in the north and west of the country, although examples also exist in the softer rocks of south-east England. Evidence for human occupation is often located near the cave entrances, close to the rock walls or on the exterior platforms. The interiors sometimes served as special areas for disposal and storage or were places where material naturally accumulated from the outside. Because of the special conditions of deposition and preservation, organic and other fragile materials often survive well and in stratigraphic association. Caves and rock shelters are therefore of major importance for understanding this period. Due to their comparative rarity, their considerable age and their longevity as a monument type, all examples with good survival of deposits are considered to be nationally important.

The twenty-one sites in Somerset form the densest and one of the most important concentrations of monuments of this type in the country. Rowberrow Cavern is regarded as important for its rare Palaeolithic hearth material and the very extensive nature of the remaining deposits both inside and outside the cave. The wide entrance to the cave has an extensive platform outside is thought to be a collapsed extension of the cave. The cave is 6.5m wide at the entrance and continues as a gradually narrowing passage for 25m. There is a side passage leading from the left side of the main tunnel. Outside the entrance is a level platform consisting mainly of collapse material and ending in a talus. The platform is partly overlain by excavation spoil and is bisected by a narrow excavation trench, 2-3m wide and 20m long, which runs from the edge of the talus to the cave mouth. Inside the cave mouth is a deep rectangular excavation trench cut into the entrance deposits. Excavations carried out by Taylor between 1920 and 1926 revealed beneath a `cemented floor’ a 2m spread of Palaeolithic hearth material, including flint artefacts. Importantly, this was recorded as continuing into the unexcavated deposits towards the back of the cave. Also recorded from higher levels in the cave were Iron Age and Roman remains. The monument includes all deposits inside the cave from the entrance to 25m into the interior, and outside the cave includes the deposits of the platform (Historic England, online. Accessed 14th November 2022)

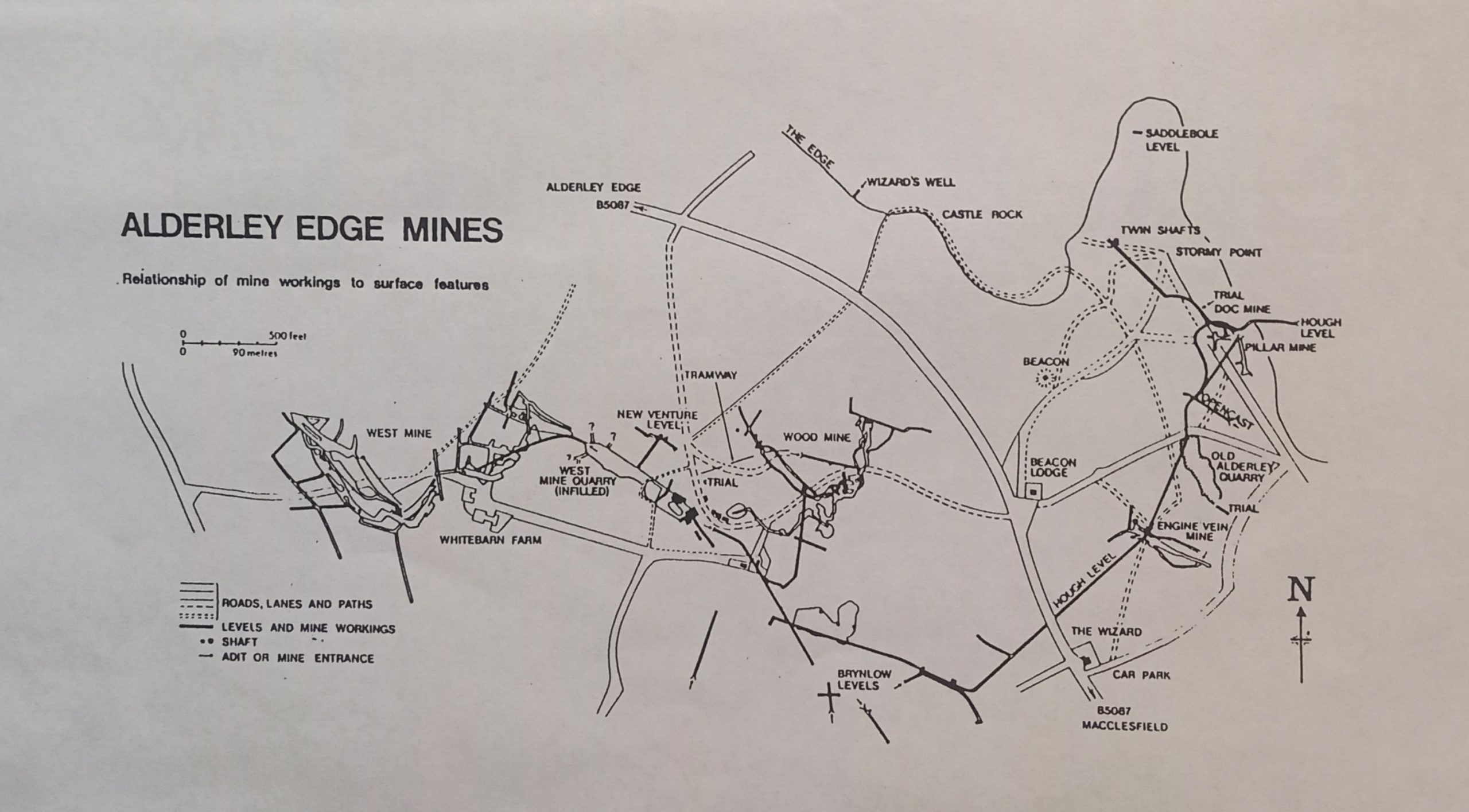

Alderley Edge Mines, Cheshire

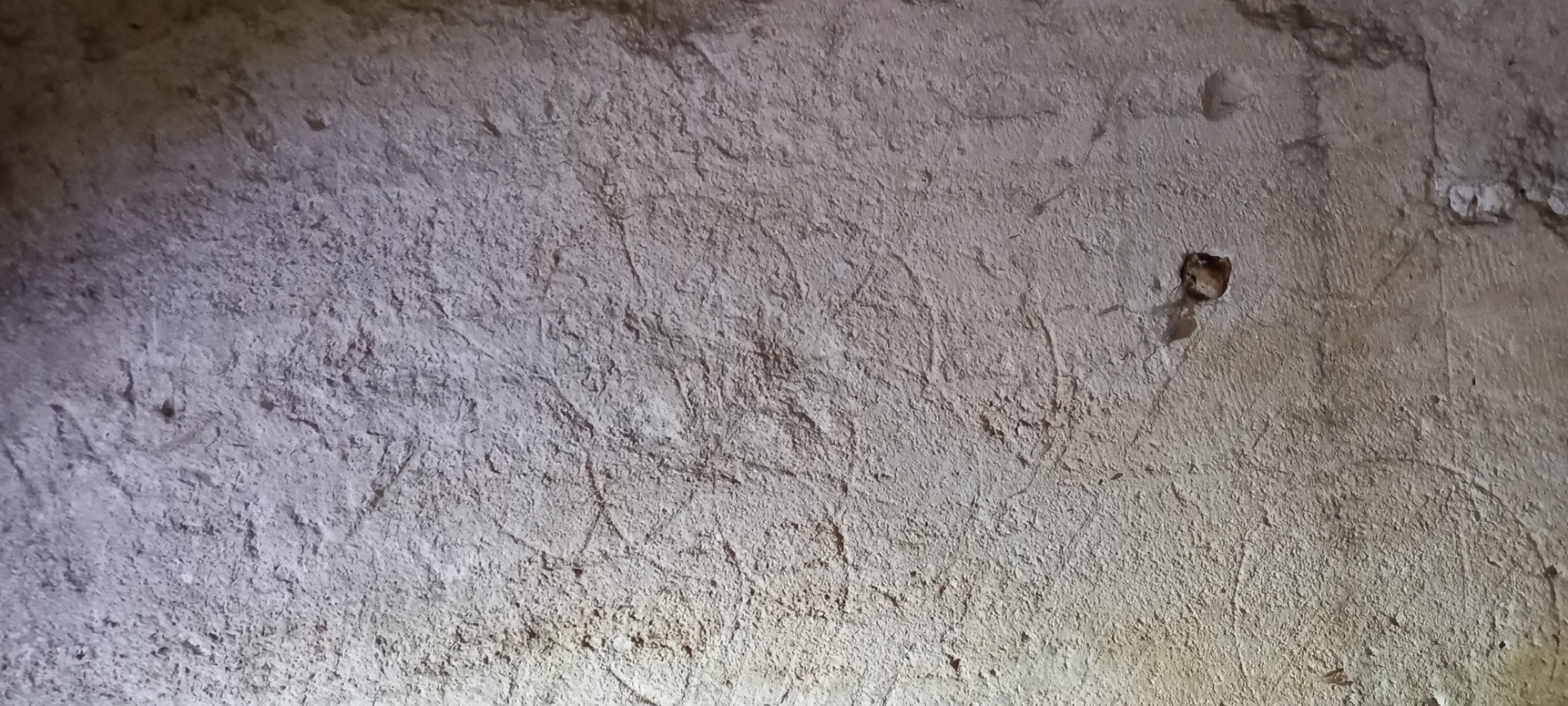

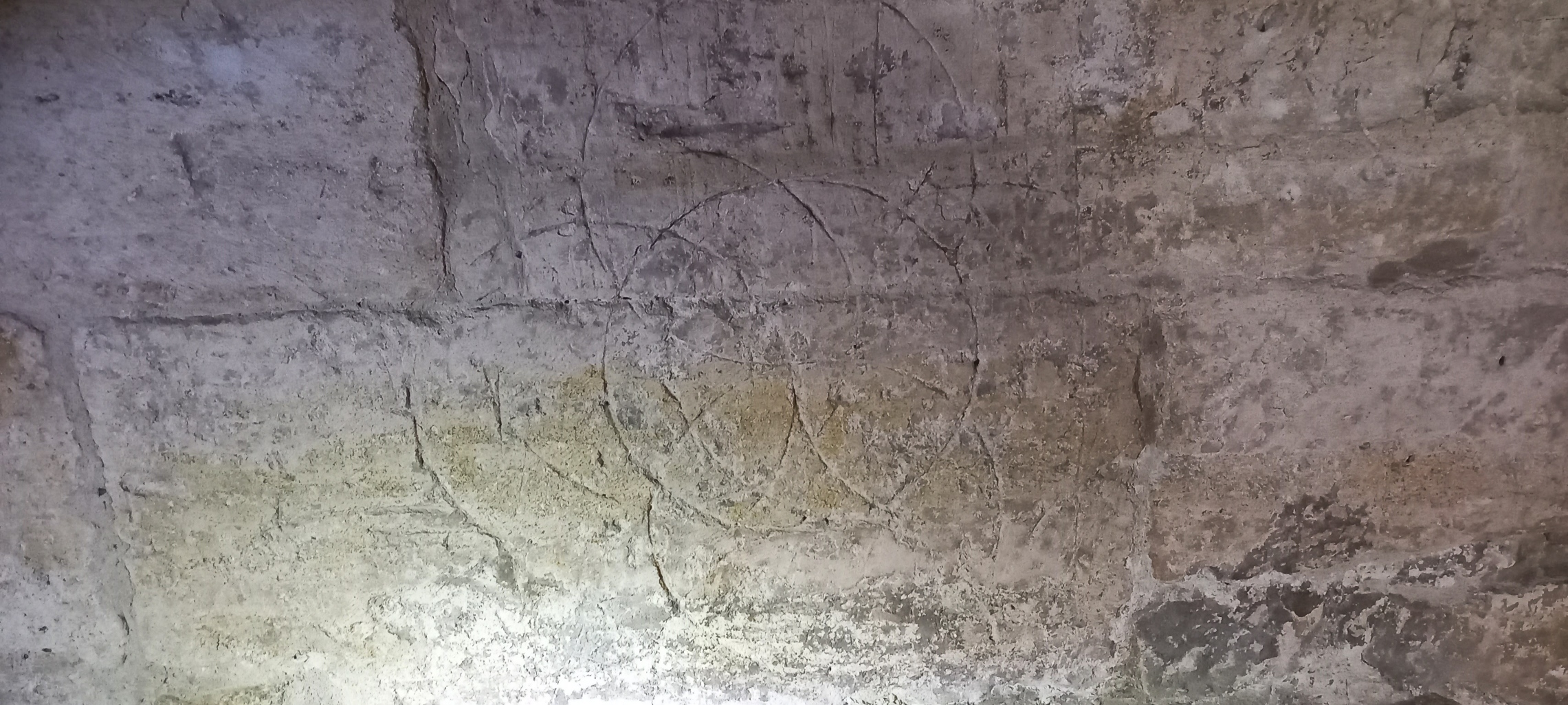

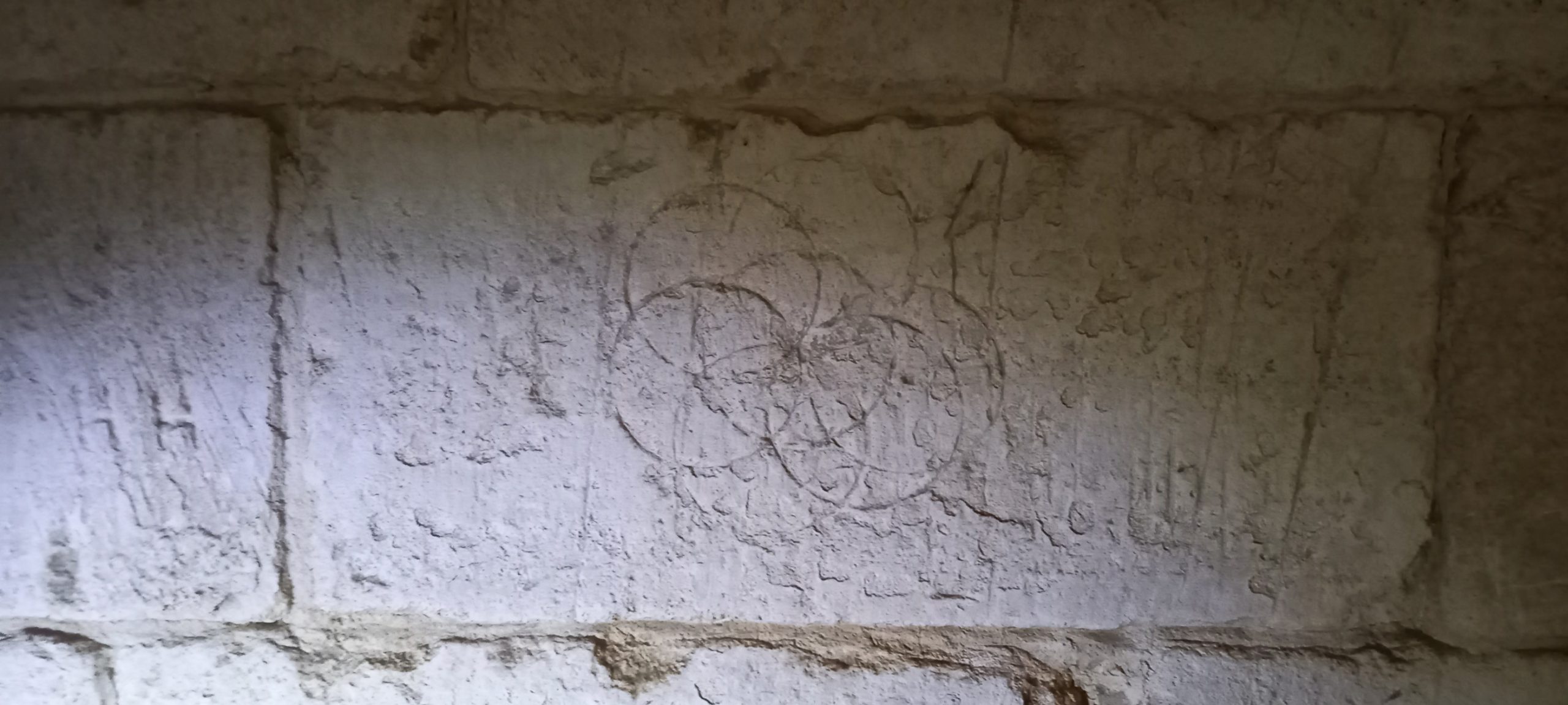

All the images below were taken during a British Cave Research Association (BCRA) field meeting on 9th October 2022.

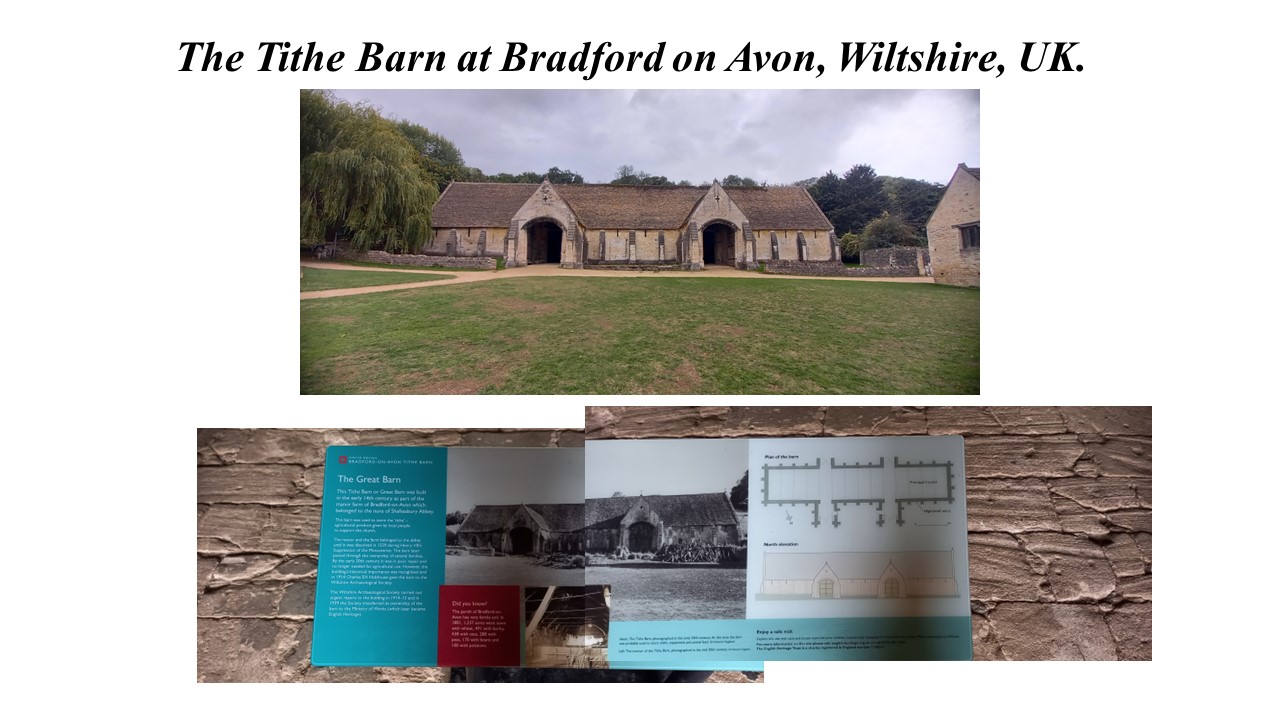

Historic Graffiti at The Tithe Barn, Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire, England.

The following historical background and description can be accessed from the English Heritage website at History of Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk

The images of graffiti and inscriptions were taken by mendipgeoarch on 27th September 2022.

“HISTORY OF BRADFORD-ON-AVON TITHE BARN

Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn is one of the largest medieval barns in England, and architecturally one of the finest. It was built in the mid-14th century to serve Barton Grange, a manor farm which belonged to Shaftesbury Abbey in Dorset, the richest nunnery in medieval England. After the abbey was suppressed in 1539, the barn passed into private hands, and was part of a working farm until 1914. See English Heritage plan of the tithe barn

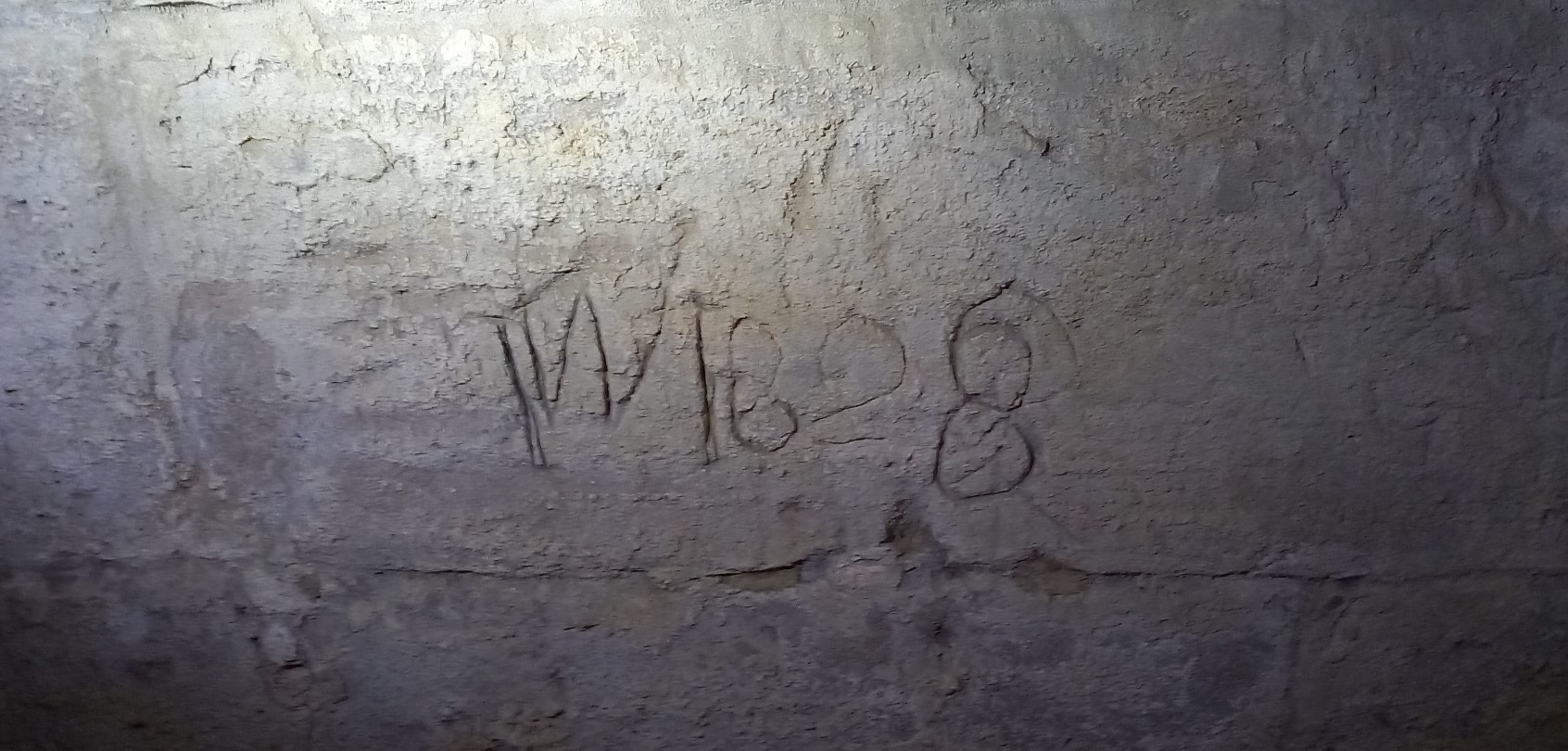

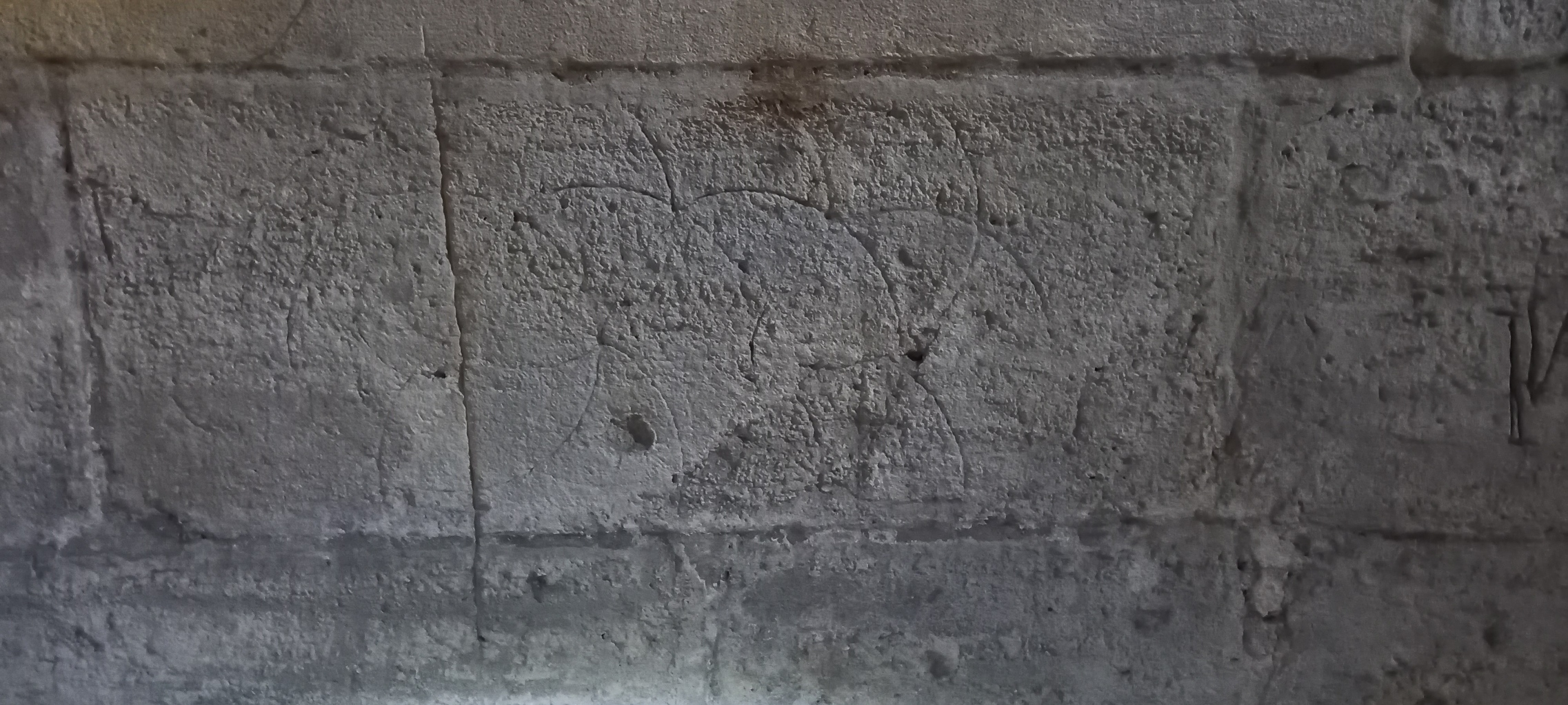

SOME EXAMPLES OF GRAFFITI/INSCRIPTIONS OBSERVED (see also Appendix below)

EARLY HISTORY

The name ‘Bradford’ means the ‘broad ford’ on the Avon. The earliest mention of the place is in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for AD 652, which refers to King Ceanwalh of Wessex fighting a battle at Bradford on the Avon, but this does not necessarily mean that a settlement existed there.

One had certainly appeared by 1001, when King Æthelred ‘the Unready’ (r.978–1016) granted the manor of Bradford, consisting of lands, the parish minster (religious community) and adjacent town, to the nuns of Shaftesbury Abbey, one of the richest religious houses in England. He made the gift in honour of his half-brother, King Edward ‘the Martyr’, who had been murdered in 978, probably by Æthelred’s mother’s retainers. Æthelred stipulated that Edward’s bones should be enshrined at Bradford, where they might be venerated, although there is no evidence that the martyred king’s remains were ever brought there.

The manor of Bradford-on-Avon was very large. The Domesday Survey of 1086 reckoned it at 42 hides, with an outlying estate of another 7 hides. There was land for 40 ploughs, 8 of which belonged to the manor farm, Barton Grange. The whole manor was worth £60 a year, making it an outstandingly valuable property.

THE TITHE BARN

Barton Grange was a notably large and well-equipped manor farm. It must have had substantial buildings through the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries, although little archaeological evidence from this early has been found on the site. An early barn, just under 43 metres (140 feet) long, was built probably in about 1300. This would have been dwarfed by the new, great barn.

The great barn has been dated to the 1330s, although there is no known documentary evidence for its building. It was probably built because Shaftesbury Abbey had secured control of the rectory (the parish church and its associated lands) at Bradford-on-Avon in 1332, and thus of its tithes – the tenth part of the property’s agricultural produce to which the rector was entitled. So, although the barn was part of a manor farm, it is probably correct to style it a ‘tithe barn’.

Accounts for five of the years between 1367 and 1392, when Joan Formage was abbess, reveal much about the management of the manor and farm. An inventory for 1367 states that there were 21 keys to the farm as a whole, including two for the ‘great barn’. These were probably for the side entrances into its north porches.

The farm and manor were valuable to Shaftesbury Abbey. A 1535 Crown survey of all monastic properties in England noted that the manor of Bradford-on-Avon produced an annual income of £154 5s 4d.

A lithograph showing the town of Bradford-on-Avon in the mid-19th century, with Barton Farm in the foreground. The newly built Kennet and Avon Canal runs parallel to the tithe barn© Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre

THE SUPPRESSION OF SHAFTESBURY ABBEY

Shaftesbury Abbey was closed as part of the Suppression of the Monasteries in 1539. In 1546, Henry VIII granted Bradford-on-Avon manor to Sir Edward Bellingham, a gentleman of the Privy Council. Upon Bellingham’s death in 1551 it reverted to the Crown.

Over the next 80 years, the manor passed through several hands, although it was never occupied as a principal residence. In 1635 it passed to William Paulet, Marquess of Winchester. The Paulets then held the manor and the barn until 1774, when they sold it to the neighbouring landlord, Paul Methuen of Corsham. In 1850 the manor was bought by Sir John Cam Hobhouse, Baronet, later 1st Lord Broughton. The lordship of the manor has remained in the Hobhouse family ever since.

Throughout these changes of ownership, Barton Farm continued to be a large working manor farm, occupied by tenant farmers. It is unclear how the barn itself was used. It did not have any suitable defences against vermin, so it may be have been used for cattle, or their fodder, or to store equipment, rather than for storing crops.

END OF USE

By 1914, the barn was no longer required for the manor farm. However, its outstanding historic and architectural value began to be recognised. Reginald Hobhouse, as agent for his father, Sir Charles Hobhouse, Baronet, wrote to Alfred Burder, a local antiquary, to inform him that:

The Barn at Barton Farm was no longer required for the use of the farm, and that Sir Charles was not prepared to spend the necessary money to put it in repair but was willing to hand it over to any Society that was willing to do so; failing this, the only alternative would be to demolish it, which it would seem a pity to do.

Burder wrote to Charles Peers, Principal Inspector of Ancient Monuments for the Office of Works, who sent a surveyor down to inspect the barn. Peers said that if costs were met for immediate repairs to be carried out, the Office of Works might be willing to take responsibility for the building. This initiative was overtaken by the outbreak of war in 1914.

The Wiltshire Archaeological Society then came to the rescue, and agreed to take responsibility for the building, which Sir Charles transferred to them in the same year.

REPAIR AND CONSERVATION

The Wiltshire Archaeological Society commissioned the eminent conservation architect Harold Brakspear to survey the barn. He noted that the original design of the building, which did not include any adequate tying-in of the roof trusses, had caused the walls to spread outwards over a long period. The barn’s owners had made many attempts to address this in the past, adding struts and ties, and extra buttresses. Nevertheless, Brakspear concluded that:

the building is anything but secure, and the tiling is in a deplorable state, and lets in the weather, which, in a short time, will rot all the timbers. Besides the faulty construction of the roof, a most alarming defect occurs in the condition of the couples themselves. These have a considerable amount of their lower parts embedded in the walls, where they rest on templates, and it seems that the whole of this portion of the walls is quite rotten, so that these heavy couples … may collapse at any moment.

The Society launched a successful appeal in Wiltshire and beyond for funds. The repairs, which included the replacement of a good deal of decayed timber, were carried out between 1914 and 1915.

Financial constraints led the Society to transfer ownership of the barn to the Ministry of Works in 1939, and the Ministry carried out major repairs in the 1950s.

REFERENCES

RB Pugh and E Crittal (eds), The Victoria County History of Wiltshire, vol 7 (London, 1953), 12 (accessed 13 Nov 2015)

J Morris (ed), Domesday Book, Wiltshire (Chichester, 1979), 39; Pugh and Crittal, op cit, 12–13

J Haslam, ‘Excavations at Barton Farm, Bradford-on-Avon, 1983: interim report’, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, 78 (1984), 120–21; M Heaton and W Moffatt, ‘Recent work at Barton Grange farm, Bradford-on-Avon’, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Magazine, 97 (2004), 211–17 (accessed 13 Nov 2015)

B Harvey and R Harvey, ‘Bradford-on-Avon in the 14th century’, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, 86 (1993), 118–29 (accessed 13 Nov 2015)

J Caley and J Hunter (eds), Valor Ecclesiasticus Temp. Henry VIII. Auctoritate Regia Institutus, vol 1 (London, 1810), 278

AWN Burder, ‘The mediaeval tithe barn, Bradford-on-Avon: report on the work of repair’, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, 39 (1915–17), 485–90 (accessed 13 Nov 2015)”

History of Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk) Accessed 28 September 2022

APPENDIX

John o’Groats to Land’s End, August 2022.

To celebrate reaching State Pension Age on 25th August 2022, we decided to go for a bike ride. It was an amazing experience. Below is my personal summary account of the journey.

Observations at Sherford Cave, near Plymouth, Devon, England.

Centred on NGR SX 5476 5377

Published in Descent (285) April/May 2022 pages 34-37

Introduction:

A doline and associated network of cave passages were uncovered during infrastructure works for a major building development at Sherford, near Plymouth, Devon. In late July 2021, the author was asked to undertake a site visit and assessment when it was established that the talus material within the doline and cave passages, contained an important faunal assemblage. There followed several subsequent visits before archaeological/palaeontological investigations were commenced in November 2021.

This summary provides a general description of the cave and some observations on the cave formation processes. The faunal remains are currently undergoing specialist analyses and a separate, full report on the findings are expected to be published in the future.

Geology:

The underlying solid geology consists of Middle Devonian Limestone formed 385 to 398 Ma when the local environment was dominated by shallow carbonate seas in the Devonian Period. In the surrounding area are outcrops of pyroclastic, basaltic, igneous rocks (Middle Devonian Slates) also formed 385 to 398 Ma, these forming in an environment dominated by explosive eruptions of silica-poor magma. Also, in the wider area are superficial deposits consisting alluvial clay, silt, sand, and gravel formed during the Quaternary Period up to 2 Ma, isolated remnants of this material are likely be found locally, possibly filling other sinkholes (BGS online).

The cave:

The open sinkhole, or doline, formed by collapse of the cave roof, is situated on a line of weakness along a fault fracture. From the bottom of the doline, an opening in the south wall leads downslope to gain access into roomy chambers to the east- and west-sides. To the east, a boulder-strewn walking size passage with some fine speleothems trends in a north-easterly direction passing a talus slope with a visible connection to the doline. A 5m climb up at the end leads into lowering passages that close down, eventually becoming too tight, the route is partially blocked by rubble from borehole works. On the southern side of the east chamber, a short climb over large boulders leads into the approximately 45m long south passage passing through a wriggle to The Last Rip. This passage is a mix of stooping, walking, and crawling among and over sharp and jagged boulders, along the way there are some decent calcite formations.

To the west side of the entrance slope, another roomy chamber with boulder-strewn floor, contains a fine white calcite drape in the roof. On the west side of the chamber a crawl, wolf passage, eventually becomes too tight. A small alcove on the northern side leads to a short 4m climb to gain access to a narrow rift, moving forward a couple of metres, followed by a tight climb down a small, decorated chamber is reached. This leads to another boulder floored chamber, on the north-side a 4m climb up through a small opening and climb down into the impressive Izzy’s Big Chamber, approximately 40m long, up to 12m wide and averaging 5m-6m high. This chamber is partitioned by massive boulders essentially into two sections, to the southwest a climb over boulders drops into the airy south-west section where possible cryogenic calcite was noted. The north-east section contains some very nice speleothems especially at the northern extent. A wriggle through one of a number of narrow holes leads to a continuation that soon closes down becoming sediment filled. A north/south rift links to the doline at the southern extent, this was probable another access route before the doline became filled.

Throughout the accessible passages the effects of modern intrusions from piling-works and boreholes are evident in the form of copious dust covering, grout and concrete overspill.

The extensive and complex cave system appears to be of hypogenic origin with the occurrence of later epigenic processes. Hypogenic speleogenesis is the formation of solution-enlarged permeability structures by waters ascending from below in leaky confined conditions, where deeper groundwaters in regional or intermediate flow systems interact with shallower and more local groundwater flow systems. Hypogenic caves are identified in various geological and tectonic settings (Klimchouk, 2009). There are no clear hydrological feeders to the system, later flow appears to originate down fissures. The cave walls show morphologies including semi-isolated chambers separated by lows blind terminations, domed roofs, large wall scallops, wall pockets, pierced partitions, bridges, and stepped wall-facets typical of slow convective currents of air or water. Many of the features are typical of initially isolated voids that have become integrated over time (Smart and McArdle, 2019). Botryoidal speleothems (cave popcorn) are a late phase secondary calcite precipitation which is often but by no means uniquely associated with hypogenic cave systems (Smart and McArdle 2019) are abundant throughout the cave network.

The cave deposits:

The open sinkhole is partially filled with talus (scree) that slopes downwards into the cave system below. It consists of mixed red, grey, and brown silty sandy gravel, cobbles, and boulders, thermoclastic in origin (the product of freeze/thaw processes). Granular material is angular to subangular, some tabular, of limestone. The talus material contains numerous bone fragments from a wide range of species, and within the cave, on the surface of the talus slope can be seen faunal remains. There is noticeable calcite deposition (flowstone) of the talus slope, especially deeper into the cave, and much of the granular material, including bones, has become cemented. Finer sediments below the coarse granular material might contain micro-fauna and human artefacts.

Faunal remains so far recovered and identified include woolly mammoth, wolf, woolly rhinoceros, horse, reindeer and hyaena. The faunal assemblage is suggested to originate from the Middle Devensian (MIS 3) period, c.60 to 20ka (Schreve, pers comm). At this time Homo sp. return to Britain. Pin Hole, Creswell Crags in Derbyshire is the defining locality for the Stage 3 faunal grouping. The Pin Hole mammal assemblage-zone (50 – 38 ka) includes woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, wolf and bovid, as well as mountain hare, red-cheeked suslik, red fox, brown bear, stoat, polecat, spotted hyaena, lion, wild horse, giant deer, and reindeer. Humans are represented as part of the of the Pin Hole mammal assemblage-zone by skeletal material at Kent’s Cavern and Paviland and by artefacts of Middle and Early Upper Palaeolithic types at more than thirty other localities (Currant & Jacobi, 2001). Similar faunal assemblages have been identified to the west of Sherford Cave at Cattedown Caves, Plymouth (LEN 1021406) and south-east at Kitley Caves near Yealmpton (Freeman, 2015).

Evidence for the effects of Pleistocene frost and /or ice.

During the Pleistocene period, interglacial and warmer interstadial periods allowed the precipitation of calcite carbonate (CaCO3), resulting in speleothem (including stalagmites, stalactites, and flowstone) growth within caves in the region generally. The following glacial or stadial periods may have resulted in periglacial activity in the cave, during which the calcite layers became fractured by freeze /thaw processes. The term ‘periglacial’ is widely used to refer to those regions where frost action constitutes the dominant geomorphological process. Cyclic freeze-thaw activity, the growth of ground ice, and the presence in many (but not all) periglacial environments of permanently frozen ground, permafrost, leads to the development of a suite of highly distinctive deposits, sedimentary structures, and landforms. It has been suggested that permafrost in caves might have reached considerable depth, consequently forming an ice plug. During the following interglacials, thawing might occur to a lesser depth. Effectively the cave would be ‘plugged,’ causing meltwater to ‘pond’ or outflow. During the build-up of ice, as it freezes ice swells, during subsequent thawing episodes, the melting ice might flow and slide, thereby causing stalactites and curtains to be sheared off the roof and stalagmites tipped over or sheared off their bases and displaced. Lumps of calcite enclosed in ice can be deposited on inclined surfaces or be left in precarious positions which would not be stable if deposited by falling, for example, during earth movements (Simmonds, 2019). Some of these fractured, displaced, and redeposited speleothems can become cemented during later precipitation periods. Izzy’s Big Chamber contained several deposits of possible cryogenic calcite and samples of these were taken as well as reference speleothem samples.

Sources consulted:

British Geological Survey (BGS) Geology of Britain viewer: Accessed 22nd August 2021 https://mapapps.bgs.ac.uk/geologyofbritain/home.html

Currant, A. and Jacobi, R. 2001. A formal mammalian biostratigraphy for the Late Pleistocene of Britain. Quaternary Science Reviews 20 (2001) 1707-1716

Freeman, J. 2015. William Buckland’s connections to the last surviving Pleistocene collections from Yealm Bridge Caverns, Devon. The Geological Curator, Volume 10, No. 4 147-158

Klimchouk, A. 2009. Morphogenesis of hypogenic caves. Geomorphology 106 (2009) 100-117

Schreve, D. Head of Department and Professor of Quaternary Science, Royal Holloway University of London. Editor of Quaternary Science Reviews. Personal communications, August 2021

Simmonds, V. 2019. Evidence for Pleistocene frost and ice damage of speleothems in Hallowe’en Rift, Mendip Hills, Somerset, UK. Cave and Karst Science, Vol.46, No.2, p74-78. Transactions of the British Cave Research Association

Smart, P.L. and McArdle, S. 2019. Geomorphology of Denny’s Hole and associated caves, Crook Peak, West Mendip: A newly recognised hypogene cave complex. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Spelaeological Society, Vol.28, No.1, p65-102