British National Grid ST 5353 4811

[A similar version of this report has previously been published in Caves & Karst Science Vol. 52 (1), 2025, p.27-31. Transactions of the British Cave Research Association (BCRA)]

Abstract

Excavation for speleological purposes is an intrusive process and as such it is vital that sediments and other deposits contained within caves are recognised, recovered where necessary, fully recorded and reported so that information about them is not lost and can be disseminated allowing for further research. During the ongoing excavation and exploration of Hallowe’en Rift, Mendip Hills, Somerset, a faunal assemblage has been recovered comprising steppe bison Bison priscus, brown bear Ursus arctos and ?horse Equus ferus. The assemblage is consistent with those found from nearby sites, such as Hyaena Den and Rhinoceros Hole, and taken together with U-series dating of speleothems suggest a Mid-Late Devensian date, MIS 3, c.59 – 24 ka. A Pleistocene date for the faunal assemblage recovered from Hallowe’en Rift further extends the list of ice age mammalian faunas found in Mendip cave sites.

Figure 1. Survey of Hallowe’en Rift and locations of faunal remains. Survey BCRA Grade 5c by D. Price, R. Taviner & V. Simmonds (latest update August 2024)

Introduction

Hallowe’en Rift, at British National Grid coordinates ST 5353 4811 and altitude 148m above Ordnance Datum (aOD), is located in a wooded hillside lying to the north-east of the Wookey Hole Cave ravine (Mendip Hills, Somerset). Excavation of the cave was commenced in 1982, but by the end of the 1980s interest at the site had waned. Then, in the early 1990s activity in the cave re-commenced briefly until interest, once again, waned as the participants moved onto pastures new. In 2009, the current phase of activity began, this phase of work concentrated on expanding the cave to the east-side of the entrance where significant discoveries were made in 2018. The exploration and investigation of Hallowe’en Rift remains an ongoing project and several potential leads, currently in the Soft South area, are being actively pursued (2024). The cave consists mostly of low passages, either partially or completely filled with sand, silt and clay containing cobbles and boulders of dolomitic conglomerate and frequent fragmented speleothems, including stalagmites, stalactites, and flowstone. The accessible low passages generally trend northeast/southwest, occasionally intersecting rifts, aligned northwest/southeast.

Faunal remains

The majority of the faunal remains so far recovered from the excavation of Hallowe’en Rift consist of Brown bear Ursus arctos, comprising a sub-adult and an adult (Professor Danielle Schreve, personal communication). As mentioned previously, a fragment of mineralised bone recovered from the spoil heap is probably of wild horse Equus ferus, although the recovered fragment is small.

| Element | Number | Element | Number |

| Epiphysis (unfused) | 3 | Vertebra | 3 |

| Phalanx | 26 | Astragalus | 1 |

| Metapodial | 20 | Calcaneus | 1 |

| Tarsus | 3 | Humerus | 1 |

| Carpus | 1 | Scaphoid | 1 |

| Tooth | 6 | ||

| Total number of identified elements: | 66 | ||

Table 1. Number of identified elements (Ursus arctos) recovered from Hallowe’en Rift, beyond Trick or Treat up to the end of 2024 when excavation was postponed due to adverse conditions.

The brown bear remains recovered so far consist mostly of ‘foot’ bones (phalanges, podials, tarsals/carpals, etc.), but also includes some vertebra and dentition. The smaller sizes of these faunal remains suggest these have not been transported any distance and are more indicative of an in-situ assemblage and likely to be close to their life/death position, perhaps, speculatively, a mother and cub perishing in hibernation. There is no evidence of carnivore gnawing on any of the faunal remains so far recovered. The assemblage does, however, suggests that there was an opening to the surface somewhere nearby. There are a number of thoughts to be considered; the faunal remains were found within a sandy deposit with frequent fragmented flowstone (frost/ice damage?) then sealed by calcite deposition. For this process to occur the cave passage must have been more open than it is at present, to allow access for bears and perhaps other mammals as yet undiscovered, and for it to be later sealed by calcite precipitation. The current human access into the cave is through a narrow, blasted fissure opened in the early 1980s, it is thought unlikely any larger mammals entered via this route. Therefore, access must have occurred through another, as yet undetermined, route. Subsequent to this ‘open’ phase, the cave then becomes filled with finer sediments over an undetermined time period. A red brown clay layer covering the calcite floor is the primary fill, followed by a hiatus as a thin grey silt is deposited, this, in turn, is overlain by a composite deposit consisting of laminated/banded grey silt and red clay in fining upwards sequences (known as rhythmites) laid down with obvious periodicity and/or regularity. In Hallowe’en Rift, permafrost conditions on Mendip during the Pleistocene Epoch are thought to have penetrated to significant depth, with subsequent periods of thaw reaching lesser depths resulting in a deep impervious ice plug causing meltwater to be trapped and ‘ponded’. The ponded meltwater ‘topped up’ by the ingress of surface-derived water, probably reflecting seasonal changes (Simmonds, 2024). The ‘pulsing’ movements of the water resulting in layered sediment deposits encountered.

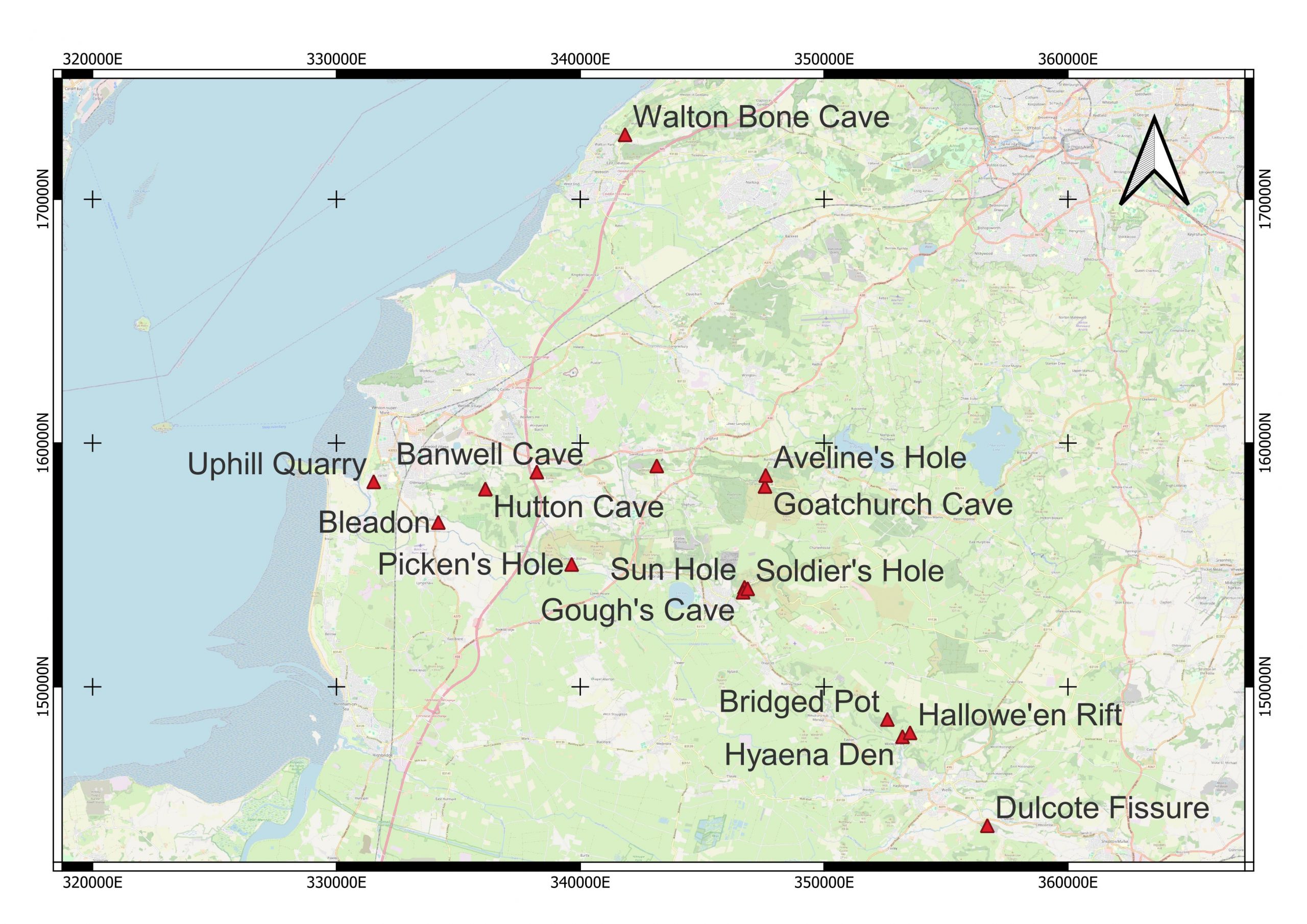

Figure 2. Mendip (and nearby) caves with faunal deposits containing remains of Brown bear, Ursus arctos (see Table 2). [OpenStreetMap contributors (2015) Planet dump [accessed 15/12/24]

Bears in [Mendip] caves

Excavations by the Natural History Museum in the 1970s at Westbury Quarry discovered an abundance of mammal bones including the extinct Deninger’s bear Ursus deningeri in deposits laid down during the early Middle Pleistocene, c.620 ka. In Britain, U. deningeri was replaced by the Cave bear Ursus speleaus after the Anglian glaciation, c.480-423 ka. which, in turn, was replaced by the Brown bear Ursus arctos appearing during MIS 9, c.339-303 ka. Faunal remains of Brown bear are relatively common in cave assemblages throughout the British Middle and Late Pleistocene during both warm and cold stages. Its presence in Britain in association with herbivores of cold open landscapes (woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and horse), as well as with those of temperate conditions, shows it to have been adaptable to a range of environments. Brown bears have evolved a generalist omnivore strategy; foraging for plants, tubers, berries, scavenging carrion, and preying on small mammals, and weak, older ungulates, and their calves. Temperature and snow conditions are reported to be the most important factors determining the composition of brown bear diet (Scott and Buckingham, 2021). Where it is still extant today the brown bear occupies a wide variety of habitats from tundra to temperate forests.

With general regard to Mendip cave sites, Brown bear (Ursus arctos) is recorded as part of the mammal fauna assigned to the Joint Mitnor Cave mammal assemblage-zone (MAZ), Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5e, c.128-116 ka, a faunal assemblage consistent with this MAZ was recovered from the nearby Milton Hill Quarry. Banwell Bone Cave MAZ (initially believed to correlate closely with the Early Devensian, c.71-59 ka, and formerly assigned to MIS 4) is assigned to MIS 5a, c. 83-71 ka. Within the Banwell Bone Cave MAZ, the remains of Ursus arctos appears to represent a larger form of the species. Brown bear has also been recorded from the Lower Cave Earth deposits at Pin Hole, Creswell Crags, Derbyshire and, therefore, listed as part of the Pin Hole MAZ, Middle Devensian, MIS 3, c.59-24 ka. The Pin Hole MAZ also includes steppe bison (Bison priscus) and wild horse (Equus ferus). Mendip sites with faunal assemblages attributable to the Pin Hole MAZ include sites near to Hallowe’en Rift at Hyaena Den and Rhinoceros Hole at Wookey Hole, and further afield at Picken’s Hole near Compton Bishop, and Uphill Quarry in North Somerset (Jacobi and Currant, 2011). It is likely that the Hallowe’en Rift faunal assemblage comprising brown bear, steppe bison and wild horse can be attributed to the Pin Hole MAZ and was deposited during the later stages of MIS 3. Brown bear also occurs in deposits attributable to the Gough’s Cave MAZ, MIS 2, c. 12.9-9.9 ka (Currant and Jacobi, 2001) in Cheddar, Somerset.

| Site (Mendip Hills area) | NGR (ST) | Age | Age (ka BP) |

| Bleadon | 3418, 5674 | MIS 7 | 245 – 186 |

| Hutton Cave | 3611, 5811 | MIS 7 | 245 – 186 |

| Picken’s Hole | 3965, 5502 | MIS’ 5a and 3 | c.83 – 24 |

| Banwell Cave | 3822, 5881 | MIS 5a | c.83 – 71 |

| Goatchurch Cavern | 4758, 5822 | Devensian | 116 – 11.55 |

| Hyaena Den | 5322, 4795 | MIS 3 | 59 – 24 |

| Sandford Hill | 4314, 5906 | MIS 3 | 59 – 24 |

| Dulcote Fissure | 5670, 4430 | Devensian | 116 – 11.55 |

| Uphill Quarry | 3153, 5841 | MIS 3 | 59 – 24 |

| Sun Hole | 4674, 5408 | 12378 BP | – |

| Gough’s Cave | 4668, 5388 | c.12200 BP | – |

| Soldier’s Hole | 4687, 5402 | Late Glacial | 24 – 11.55 |

| Bridged Pot | 5260, 4866 | Late Glacial | 24 – 11.55 |

| Walton, Clevedon | 4184, 7265 | Late Glacial | 24 – 11.55 |

| Aveline’s Hole | 4761, 5867 | Late Glacial | 24 – 11.55 |

Table 2. The occurrence of Brown Bear Ursus arctos in archaeological sites in the Mendip Hills area. Dating of most records is indirect (adapted from Yalden, 1999, Table 4.3, pp. 113-115)

Dating

Speleothems from Hallowe’en Rift have been sampled and uranium-series dates obtained spanning MIS’s 15-13, 7c, 5e and 3, with the youngest date 51.26 +0.31 −0.32 ka (Simmonds, 2019). The spread of dates suggesting that the passages in Hallowe’en Rift were open for long periods during the Early to Late Pleistocene before becoming filled with sediment through the latter part of the Pleistocene and continuing throughout the Holocene.

In January 2025, an application to fund radiocarbon dating was accepted by the British Cave Research Association (BCRA) Cave Science and Technology Research Fund (CSTRF). A sample, consisting of a partial canine tooth, was selected and sent for analysis. Unfortunately, the sample failed due to a lack of collagen in the sample making it unsuitable for radiocarbon dating. The lack of collagen might be due to several factors including the age of the sample was beyond the limits of radiocarbon dating (c.50 ka) or mineralisation of the faunal remains recovered. It is hoped that another sample might be found that is suitable and sent for radiocarbon dating in the near future.

The faunal assemblage from Hallowe’en Rift comprising steppe bison Bison priscus, brown bear Ursus arctos and ?horse Equus ferus is consistent with those assemblages recovered from nearby sites, such as Hyaena Den and Rhinoceros Hole that have been attributed to the Pin Hole MAZ, Middle Devensian, MIS 3, 59-24 ka. In the absence of absolute dating a Middle Devensian date is suggested for the Hallowe’en Rift faunal assemblage including Ursus arctos.

Comments

In Britain, the faunal assemblages recovered and identified from cave sites are a valuable resource providing useful information and adding to the understanding of past environments and how organisms adapted to fluctuations between cold glacial and warmer interglacial periods. A Pleistocene date for the faunal assemblage recovered from Hallowe’en Rift further extends the list of ice age mammalian faunas reported from Mendip cave sites.

The excavation of caves for speleological purposes is an intrusive process, as such, it is vital that sediments and other deposits contained within caves, in this case faunal remains, are recognised, recovered where necessary, fully recorded and reported so that information about the deposits is not lost and can be disseminated widely and so allowing for further research.

Acknowledgements

Without the commitment, determination, and camaraderie of a dedicated group of diggers, including (in no particular order) Graham ‘Jake’ Johnson, Paul Brock, Nick Hawkes, Robin Taviner, Jonathon Riley, Mike Moxon, and Roz Simmonds, the discoveries made in Hallowe’en Rift could not have happened.

A special thanks to Professor Danielle Schreve (University of Bristol) who is always ready to give advice and confirm identification of faunal remains whenever asked.

Thanks are extended to the anonymous reviewer(s) whose comments added to the clarity of this report.

Map data copyrighted OpenStreetMap contributors and available from https://www.openstreetmap.org

References

Currant, A. and Jacobi, R. 2001. A formal mammalian biostratigraphy for the Late Pleistocene of Britain. Quaternary Science Reviews 20 (2001), Elsevier Science Ltd. 1707-1716

Jacobi, R and Currant, A. 2011. The Late Pleistocene Mammalian Palaeontology and Archaeology of Mendip. In Lewis, J. (Ed.) The Archaeology of Mendip: 500,000 years of continuity and change. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK

Kearey, P. 2001. The New Penguin Dictionary of Geology, 2nd Edition. Penguin Books

Scott and Buckingham. 2021. Stanton Mammoths and Neanderthals in the Thames Valley: Excavations at Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire. Archaeopress Archaeology

Simmonds, V. 2019. Evidence for Pleistocene frost and ice damage of speleothems in Hallowe’en Rift, Mendip Hills, Somerset, UK. Cave and Karst Science, Vol.46, No.2, (2019) 74-78. Transactions of the British Cave Research Association

Simmonds, V. 2021. A brief note on faunal remains from Hallowe’en Rift, Mendip Hills, Somerset, UK. Cave and Karst Science, Vol.48, No.3, (2021) 95-96. Transactions of the British Cave Research Association

Simmonds, V. 2024. Notes and observations relating to sediments containing ferro-manganese spherules found in Hallowe’en Rift, Mendip Hills, Somerset, UK. Cave and Karst Science, Vol.51, No.3, (2024) 129-133 Transactions of the British Cave Research Association

Yalden, D. 1999. The History of British Mammals. T & A.D. Poyser Ltd. London

All photographs by the author unless stated otherwise.

A representative selection of photographs: